The history and ecology of Vancouver’s big trees are alive and accessible at Vancouver’s heavily forested Point Grey Peninsula. Nearly all of the area was once logged, but at different times, and many old-growth giants still remain. This guide shares with you the unfolding story of forests at UBC campus and in surrounding Pacific Spirit Park. Basic maps and directions are provided for you to discover remarkable old-growth trees and legacy stumps.

These are the contents of this guide:

-

Visit the remaining old-growth and search for the biggest tree

1.1 Wreck Beach Forest

1.2 Southwest groves

-

Logging and forest regrowth. A story of human disturbance legacies and future forest giants.

2.1 The Great Stumps

2.2 Future Forest Giants

-

UBC campus trees: Biggest trees on campus and the ecosystem services provided by the campus urban forest.

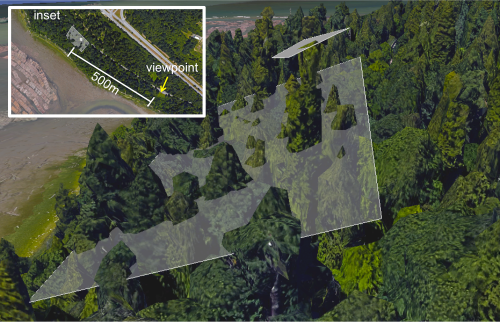

Figure 1. Outlined in green is an estimated 68 ha of the UBC peninsula that was not logged and is mostly old-growth forest containing some trees 64 m tall that may 400 years old1. VISIT THE REMAINING OLD-GROWTH AND SEARCH FOR THE BIGGEST TREE

1. Visit the remaining old-growth and search for the biggest tree.

The University of British Columbia campus is set in a clearing of a productive conifer forest. Most of the forests surrounding UBC campus have been logged off at some point. These forests left to regrow are clearly marked by a century and a half of human activities. However, there is one large swath of old-growth forest, 68 ha in area, that remains quite intact, and it contains 400 years old Douglas-fir and champion grand fir and big leaf maples. This magical old-growth forest is easily accessible and also highly visible from campus. Surrounding the south and west sides of the campus, this a wild ancient skyline is home to bald eagle and forms a distinct sense of place for UBC campus (Figure 1). This and Stanley Park are the only remaining old-growth forests immediately adjacent to Vancouver.

1.1 Wreck Beach Forest

The biggest tree in UBC (by volume) is also one of the easiest to visit. All you need to do is first arrive at Wreck beach, then walk south (left if coming down the stairs) and about 70m down is a grandose Douglas-fir emerging above the forest. In 2012, it measured 2.45m (8′) in diameter, and it’s expected to be at least 400 years old. The tree’s healthy crown absolutely towers over Wreck Beach, yet it somehow remains a hidden gem to most beach goers. The tree is unmarked but just 10 m uphill from the high tide line. To get to its base its possible to bushwack through thorny salmonberry, but if possible, you can opt to minimize treading around its sandy soils, which are sensitive to erosion. The best view of it is certainly from the beach.

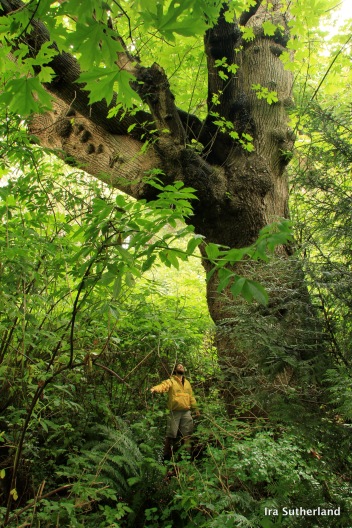

The largest tree at UBC, a 2.45m diameter giant, rises above Wreck Beach

Other notable large trees can be seen while walking the steep and long Wreck Beach stairs (Trail 6). If you wish to not hike down, then conveniently see the large, forked Douglas-fir perched at road level, just 20m south of the top of the Wreck Beach stairs. This ~46m tall tree has a dead top and huge fork, indicating that it is many centuries old. It was featured on the CBC news in a story about potential impacts to these significant trees from a forest fire at Wreck Beach in 2015. Its since earned a name, the ‘CBC fork tree.’ Just shortly down the staircase on the left see a straight tall and stunning grand fir specimen. Another, taller grand fir (~55m) and a Douglas-fir is above the trail on your right. About halfway down staircase you can still spot a burnt and broken off veteran Douglas-fir in the ravine. This giant has a width of 2.4 m DBH (Figure 4, below). This veteran tree began to grow possibly hundreds of years before the first European ship (a spanish one) sailed by its shore in 1791. Unfortunately, the final live branch on this tree died during winter 2013-2014. Old decadent trees such as this one often remain standing for many decades providing habitat for wildlife and slowly releasing their nutrients and carbon to rest of the ecosystem.

At around midway on the Wreck Beach stairs there are 4 western red cedars that have the appearance of trees that have been ‘culturally modified’ by Musqeuam First Nations. Notice the vertical triangle of bark missing on their trunks, a common mark of First Nations traditional stripping of cedar bark along the coast. However, this affect can also be naturally caused, especially on steep, sandy sites. The entirety of UBC and Pacific Spirit Park is in the traditional territory of the Musqueam First Nation. They have lived on this land, which they call Sty-Wet-Tan (meaning “Spirit of the West Wind”) since time immemorial.

Figure 2. This grand fir (Abies grandis), at 64.5 m height, is the third tallest grand fir recorded in BC. It has a complex crown, caused by an insect outbreak around the 1970’s that killed its leading shoot triggering branches to grow upwards.

Left of the dead tree, the 64.5m tall grand fir is clearly seen from the UBC Forestry Sciences Centre in 2015. This grand fir is actually much taller than the other trees beside because it’s base grows from 20m below, deep within the steep Totem Ravine.

An area known as Totem Ravine, just below the intersection of Marine Drive and the western end of Old Marine Drive contains impressive trees including a grand-fir (Abies grandis) that is 64.5m tall (Figure 2), a height only exceeded by two officially recorded grand firs in the province. This tree can be seen prominently from the surrounding portion of campus (above) and is distinguished by many branches that have begun to grow upright about 40 years ago when it was attacked by balsam wooly adelgid (Adelges piceae), an insect accidentally introduced from Europe. The leaders of most grand firs of the UBC area were killed by the adelgid outbreak in the 1960’s giving the trees oddly formed, often forked or fanned out crowns making them easy to identify from a distance.

Old-growth forest in totem ravine. Bark was burned in a 2011 wildfire that resulted in a large dead tree being cut down. Where the tree was cut, I counted its annual growth rings. It was 402 years old.

Also in Totem Ravine is the decomposing stump of a Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) snag that was 402 years old when alive. I estimated this age by counting its rings, which were exposed when the snag was cut down by fire fighters while extinguishing a small wildfire in September 2011. Its stump is 1.8 m diameter where it was cut. Farther below, towards the beach, is a sharply-leaning Douglas-fir that is 2.45m DBH. Slightly further uphill from this Douglas-fir, and in the ravine is an exceptional grand fir specimen estimated at nearly 60m in height (Figure 3, below), which also leans to the north. From the beach around there, you can gain a good perspective down the beach of the large Douglas-fir just above Wreck Beach (as mentioned above).

Figure 3. Big trees at Totem Ravine (Click to enlarge). The red line marks a closed trail that is not accessible to the public, and is blocked by a wooden fence about 20m in from Old Marine Drive.

A large Big Leaf maple below the UBC Botanical gardens, 100-150 m east of bottom of trail 7 and just into the forest away from the beach

1.2 Southwest groves

The UBC Botanical Garden (free admission for UBC Students) is a very convenient place to see some fairly large and old trees. Here you can find a very tall forked-top grand fir near the garden’s westernmost corner and an old and gnarled living Douglas-fir in the center that is often perched on by eagles. For an extra fee you can take the impressive canopy walkway that hangs almost 20m above the ground and allows you to get a rare birds eye view of the old-growth trees.

The strip of forest to the south west of the Botanical Gardens also contains many impressive trees, at least two of them support large eagle’s nests in their crowns. One of the tallest trees of the area is a tall straight grand fir forked three ways at the very top with a large eagle’s nest nestled right into the fork. This tree and the eagles nest is highly visible when going northwest along old marine drive. I estimated its height to be 63m using Google Earth and 67m based on a ground hypsometer measurement. Unfortunately, because the tree is surrounded by thick salmonberry, it is difficult to measure accurately. Nudity is not permitted in this forest, but hikers should be cautioned that during warm months it is commonly encountered and indecent behaviour is sometimes reported.

This giant grand fir is at least 62m tall and has a giant eagles nest cradled in its three way top branches. Spot it rising straight over road centre as you head north west along old marine drive.

A large and unique Douglas-fir can be seen from Wreck Beach trail #7. Near the bottom of the trail, a large Douglas-fir visible across the creek to the east has very large lateral branches and an unusual canopy structure. A small trail runs along eastern side of the creek, but this area is closed now due to erosion concerns. While you are there, from the bottom of trail #7 walk further east about 100-150m and encounter a large single-stemmed big leaf maple growing just inside the forest (photo above).

Pacific Spirit Regional Park Trail map

Wesbrook Ravine

Another spectacular old-growth area I have recently seen thanks to a tour given by big tree searcher Ralf Kelman is just below the Marine Drive 41st Highway west of its junction with Wesbrook Mall. This steep ravine has several ancient Douglas-fir that nearly rival the giant at Wreck beach. Here, we found a 46.7m tall big leaf maple – the second tallest recorded in the BC Big Tree Registry (on left below)

BC’s second tallest big leaf maple at 46.7m towers above traveller Flora Hugon, author of Life in Motion, who visited this grove to help measure these giants.

And, the highlight in Wesbrook Ravine is a spectacular grand fir near the mouth of the ravine at sea level. I measured it with a laser to be 59.6 m tall. Its live crown begins quite low at 16m, and then continues luxuriously full right up to its tip in the sky. It is 140.3cm diameter. A remarkable feature of these giants is that these trees were likely already well established when the first Europeans arrived to these shores in 1791. An astonishing aspect of these trees, which surround one of the nation’s largest university campuses, is that among the 100,000 staff, students, and residents of UBC, very few have hiked in to appreciate and connect with these stunning forest. Take a break and hike into these amazing vestiges of a world thought gone.

A map of Wesbrook ravine, which is easy to access great viewing from just a few meters in from the road.

A tip for when to visit the old-growth forests of UBC

Much of the old-growth forests of UBC are set along steep beach slopes that are difficult to explore. Hiking off trails (up the steep slopes) should be avoided due the erosion and harm this may cause for the legacy trees. I suggest that winter months, when the understory is leafless, permit the best and easiest viewing of big trees here. There is also less nudity (this is a clothing optional beach), which some visitors may prefer.

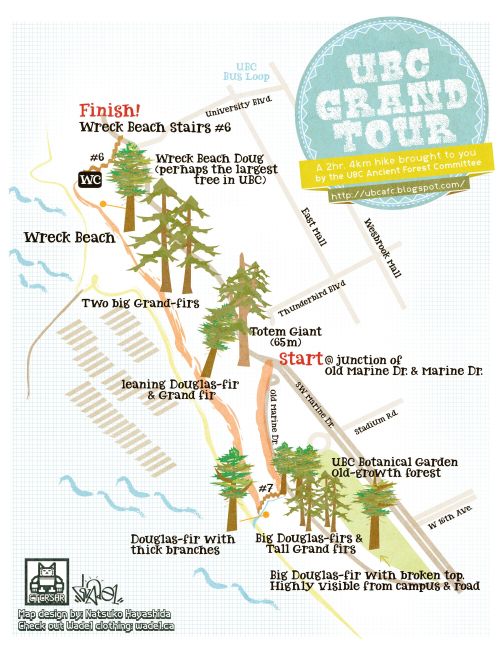

The main trail running along the shore between stairways of Trail #6 and trail #7 (trail map) is a scenic hike, unmaintained and rough. The UBC Ancient Forest Committee (AFC) recommends using the beach trail to visit many of the tallest trees along the shore based on the suggested map below (Figure 5, below). In mid-winter you may have it all to yourself.

Figure 5. Map of UBC Grand Tour. Map by Natsuko Hayashida

2. Logging and forest recovery. A story of human disturbance legacies and future forest giants.

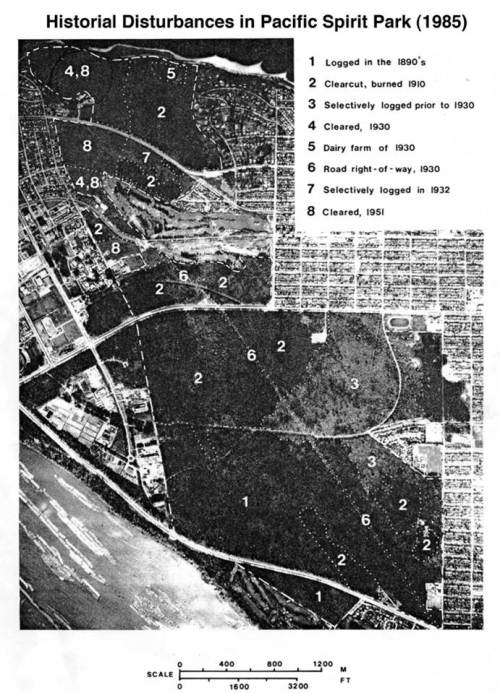

History of human disturbance in Pacific Spirit Park (Thompson 1985)

2.1 The Great stumps

The vast majority of what is now Pacific Spirit Park once contained large diameter trees. Ubiquitous large stumps provide clear evidence of past logging and indicate the remarkable size trees once obtained in the area. The largest stumps I know can be easily visited by following a trail named ‘False Lily of the Valley’ for about 70m east of its junction with the ‘Cleveland’ trail (trail map). If your walking to the west (away from Cleveland trail) the first stump you see is an impressive hollowed out red-cedar stump that measures 3.3 m diameter at breast height (DBH). Shortly beyond this is a tall standing cedar stump that died from natural causes. It is at least 1/3 rotten away at the base but still measures 2.7 m DBH. A little past this is a symmetrical cedar stump 3.0 m DBH that is concealed by moss and shrub growth. Red-cedar stumps resist rot for sometimes hundreds of years thus remaining as legacies of the past forest condition. You will also notice that these stumps clearly bear springboard notches made by loggers while cutting down the tree (as seen below), serving as clues to the human actions that shaped the forests seen today. Read more about Vancouver’s amazing super stumps.

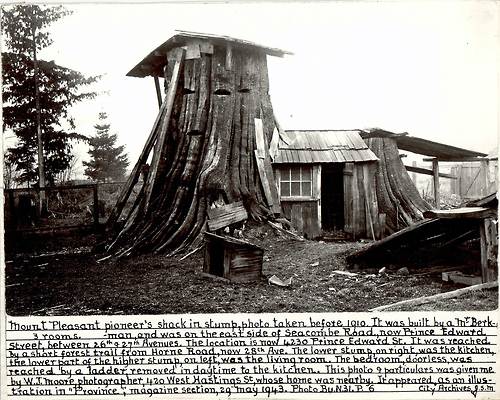

The western red cedars historically growing in the Vancouver area were so large that they were sometimes utilized by settlers to build stump houses. This incredible stump house was near the present location of Vancouver’s Queen Elizabeth park

Another area with large cedar stumps is on ‘Council’ and ‘Aims’ trail immediately to the east of the (Figure 2) Wesbrook Village development. Midway along the short ‘Aims’ trail is one cedar that died naturally leaving a stunning 2.8m DBH snag that is charred black from fires in the 1910s.

In an area that once had very tall trees, you will find other impressive Douglas-fir stumps. Walk south from the ‘Council’ junction along ‘Sword Fern’ to a Douglas-fir stump directly on the trail. This is 1.8m DBH without bark and much rotted away while across the trail and a few meters further along is a similarly degraded 2.0m DBH Douglas fir stump,. Noticeably behind this is an impressive 2.4 m DBH Douglas-fir stump with its thick bark still intact.

2.2 Future forest giants

Although vast areas of old-growth were cut, much of the forest was left to regrow becoming an extensive and now quite old second-growth forest.

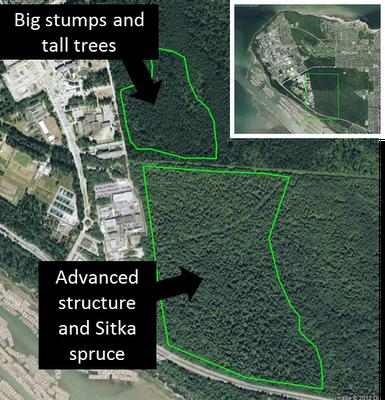

The area described above with large Douglas-fir stumps is evidently a productive site because further along ‘Sword Fern’ trail, about 20m past a park bench and 10m off to your left, is a very large, healthy and straight growing Douglas-fir. In a forest of uniform tall second-growth, this tree stands out as a big one. I measured the giant with hypsometer to be 59m tall. This is a remarkably tall tree for a forest that is 110 years old. With a diameter of 1.7m DBH, It is the largest tree I have observed in the park’s second-growth forests. Because the park contains many areas with tall second-growth trees I previously thought it would be very difficult to confirm which is the largest or tallest. However, I’ve now used a Google Earth 3d canopy model, which is proven quite accurate for measuring tree heights on relatively level ground. With help of Micah Ewers, I’ve since identified on Google Earth a collection of trees around 60m height, then ground-truthed the tallest. Many are over 60m tall. These are are within the same area (and slightly further north) labelled in the map below as “Big Stumps and tall trees.”

Forest stands like these, which are still densely treed and thus have high competition for light, will continue to gain height. As the trees continue to grow taller, other forest development processes will take place as some trees die or become knocked over by the wind. As some trees dies, their deaths will create an increasingly open canopy above and a forest stand with fewer trees, which will grow larger. The mortality of trees is a natural development process, which helps bring the light back (amazing video!) into the forest floor to support understory plant growth. This process pushes along the process of forest succession, and enhances the habitat quality and diversity of the forest ecosystem.

I located this tree in Google Earth as being 61 m tall, then ground truthed it with a hypsometer tree measurement device to be 61.1m. Astonishingly tall for a tree only 110 years old. Interestingly, this stand is a mixed stand of Douglas-fir and grand fir, and appears to be the tallest stand in the second-growth portion of Pacific Spirit Park

The southernmost portions of the park’s second-growth forest (ie. running along South West Marine Drive highway) were logged early in the 1890’s (Thompson 1985) and are beginning to develop structural attributes commonly observed in old-growth forests (Figure 2). Old-growth forests have distinct features, including the presence of relatively large trees some of which have died and become snags (dead standing trees) or fallen to the ground to become large logs on the ground. There are 26 vertebrate species or subspecies in BC that depend on snags as critical habitat (Lofroth 1998). Similarly, large fallen logs on the forest floor are required by many endangered species, two of which are found in Pacific Spirit Park: the western red backed vole (IUCN 2011) and the Pacific water shrew (BC 1995).

Vine maples (Acer circinatum) have bright yellow leaves in the fall, and there trunks do not ascend, but distinctively arch through the understory

In contrast, second-growth forests are typically quite homogeneous in structure, and lack diversity in the size, species and age of trees. In second-growth, young vigorous trees compete strongly for light. There competition results in maturing forests (like Pacific Spirit Park) to have tall trees that support a single thick canopy high above the ground, excluding light from understory plant growth.

It takes centuries for second-growth to transition into old-growth forest. The rate of old-growth development is limited by the time it takes a sequence of ecosystem processes, which includes maturation of large trees, death of large trees to provide snags, and disturbances that knock trees to the ground to form woody debris. Other recovery processes may take several hundred years. For example, formation of large canopy soil mats first requires development of large branches, then colonization by lichens and mosses (research shows it takes centuries), and finally, centuries of organic matter collection. Similarly, development of large hollow cavities used by bears and other mammals for shelter first require maturation of large trees, and then decadence and inner rot to form within those trees.

Traditional use of red-cedar by coastal First Nations provides an analogy to view the centuries long process of forest recovery. Squamish elders say that when a cedar tree is 70 years old, it can be harvested for cedar bark then left to live and heal. It will survive, and when it is 200-300 years old they can come back and split a portion of the tree for use in housing planks. When the tree is 500 years, if it is in good condition, then it can be cut down for use as a totem pole or to carve a river canoe. Or, it can be left to become a monumental 1000 year old tree at which point it may be suitable for carving large ocean going canoe.

A monumental canoe recently felled to carve traditional First Nations canoes. A total of four large ocean canoes are being carved from this single tree

In my MSc thesis, I researched the recovery time frames of forests an the multiple ecosystem services that they provide. My goal was to build a framework for understanding how forestry impacts multiple values held for the forest, by viewing the impact explicitly in terms of the length of time it takes forest values to recover. To represent First Nation’s values for the forest, I worked with a Nuch-a-nulth carver to identify the sizes and other characteristics of cedar trees used in traditional carving.

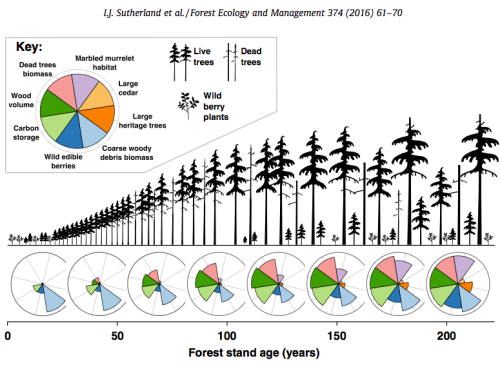

Forest recovery is a centuries-long process. In our published research, we quantified the non-linear dynamics of forest recovery for a broad suite of ecosystem services (ie. forest values).

A unique thing about the second-growth forests of Pacific Spirit Park is that they will continue to grow and recover! Unlike other second-growth forests in BC, this area is now protected and should then not be cut down again. One day it may become an old-growth forest.

Along the southern portion of the park, a large swath of forest (~50ha) is already developing old-growth attributes. This is ‘Ecological Reserve #74,’ the original conservation area (formed 1975) that formed the first step in creating the current park. It is one of the last habitats in Canada for the endangered Pacific water shrew. For it’s conservation value this reserve, is off limits entirely to the public. To see and experience this general area, however, you can follow the southernmost sections of ‘Sword Fern’ trail, which give a great view over many boardwalks into the structurally more complex, forest that is beginning to develop old-growth attributes. This ecosystem is wetter and richer than other areas upslope. The wet soil supports large Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis), a native species, which is only found in a few areas of Pacific Spirit park and is uncommon in the region due to habitat loss.

The north end of Pacific Spirit Park is not recovering well from human disturbance. Most cut portions of Pacific Spirit park were left to naturally regenerate. The northern edge, however, was cleared in the 1920’s and then again in 1951 for housing that never occurred. The forest and its soils here were mangled badly. When left to regrow, the legacies of those impacts have persisted. The area is now dominated by pioneer native broadleaf tree species with little conifer establishment. Invasive plants, such as Irish Holly (Ilex aquifolium) are pervasive under the deciduous understory. The holly seems to outcompete native shade-tolerant trees and is gaining height toward the main canopy where it then forms dense shade that eliminates any potential for other plant species to grow below it. Organizations are actively removing English ivy (Hedera helix), a noxious weed capable of climbing and eventually killing large trees. Check out Invasive Species Working Group.

A conservation concern I’ve noticed is that invasive plants may compete with the parks few Pacific yew, which grow in steep gulley slopes on the north side of the park, such as along trail #3 to Tower Beach. I’ve yet found only one mature large yew specimen, which is down West Canyon Trail near where the trail drops down into the ravine above the beach.

3. UBC campus forest. Biggest campus trees and the ecosystem services provided by the campus urban tree canopy.

The tallest trees officially on the UBC campus grounds are by far and large a collection of Douglas-fir at the very north east end of Wesbrook VIllage —an area heavily impacted by campus development (see below).

One of the tallest trees on campus, at 58m in height! Officially, the tallest is just to the left around the corner. Many other tall giants were cut down for the building of the Wesbrook Village housing development, as shown in map below.

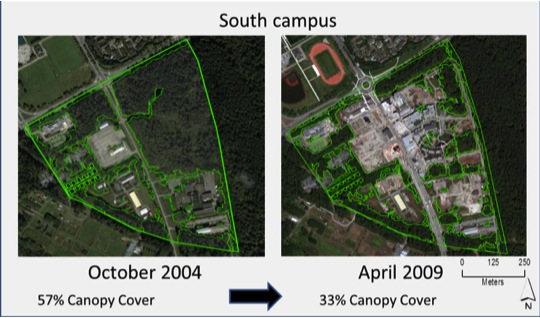

In 2012 I completed a study of the UBC campus urban tree canopy to assess the role of urban trees in campus sustainability. I used spatial analyses to assess changes in urban tree canopy cover from 2005 to 2009. I also used literature review to identify what are the benefits, or ecosystem services, provided by campus urban trees to the UBC community? The study can be found online, but here is a very brief summary:

I used an existing data set called Light image detecting and ranging (LiDAR) to determine that tree canopy covered 30% of the campus. Canopy cover was higher in the southern portion of campus where UBC farm is found, and only covered 22% of the main campus area – far below the average of 27.1% estimated for North America cities. I used existing tree inventory data to estimate that there are 207-217 species of trees (not counting cultivars), mostly non-native, in the main campus area alone.

UBC Campus arboretum in spring and large oaks in yellow spring foliage.

I also reviewed scientific literature and UBC campus planning and policy documents, to determine which ecosystem services were likely of the greatest value to UBC and the surrounding community. I then estimated the extent that those were affected by canopy reductions. Indeed, I found that trees are a dominant part of the campus environment and contribute many integral direct benefits to the university and community. Unfortunately, the campus tree canopy appears to be declining in areal extent and structural complexity. I documented significant declines in two of my study sites. For example, the Wesbrook place development in south campus resulted in the clearing of over 11 ha of tree cover from 2005-2009, of which about 60% was mature conifer forest (e.g. 90-year old trees around 55m in height). More maps of canopy change can be seen in the final report.

I investigated ongoing losses of UBC’s campus tree canopy during my undergraduate studies.

The biggest planted trees at UBC Campus

Among a campus with many nice planted trees, some of the largest non-native specimens on campus include the beloved American elms along university Blvd at Main Mall and one block north on Agricultural Road. Also, large silver maples (Acer saccharinum) line University Boulevard leading out of the campus. One of these on the north side of the boulevard at the Salish trailhead is 1.45m DBH in 2011. Impressive oaks include the specimens in the UBC arboretum and, of course, one of UBC most remarkable arboreal treasures: the nearly kilometre long line of mature red oaks lining Mainmall Avenue in the campus core.

An exquisite American elm (Ulmus americana) in the heart of UBC campus located along Agricultural Road outside the Hennings Physics building. This tree seems to defy physics itself with its immense arching branches covered in moss and liquorice fern.

The most remarkable non-native conifer on campus is the Ponderosa Pine, a legacy of the former arboretum. Unfortunately, this tree is now wrapped around on all sides by the Ponderosa Student Housing Complex (see photo below when it was still free). The largest non-native conifer is perhaps the giant sequioa (Sequioadendron giganteum) behind the First Nations building in the old UBC arboretum. Apparently, some students around 2014 have created a custom to punch and kick this poor tree. Native to the Sierra nevada mountains of California, this is the largest tree species in the world and grows fast in the Vancouver climate. It may be the largest tree on campus within coming decades

Ponderosa pine is native to BC’s interior but is sometimes planted in Vancouver. This is likely the finest specimen in the region, and that is why it was saved as high rises were built all around it. Everyone is hoping that it will survive its new environment. (photo from 2011)

Conclusion

The UBC community is set in a grove of splendid forest. By knowing that this incredible forest exists we can feel true gratitude for our setting and arrive deeper in our connection with place. These forests are written by time; they tell us stories that span centuries. The name given to this area by the Musqueam First Nations Sty-Wet-Tan (Spirit of the West Wind) speaks to the invigorating ocean side beauty of these forests and the coexistence of humans and nature. The rotting stumps tell us of greed and the lasting legacy impacts humans cause, and continue to cause, for unsustainably exploiting forests with greater value left standing. The forests around UBC are productive and can flourish resiliently, thus enabling the community to flourish along with it.

References

BC 1995. Wildlife in BC at risk: The Pacific water shrew. Access from: http://www.env.gov.bc.ca/wld/documents/shrew.pdf

IUCN 2011. Red List of Threatened Species. Access from http://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/42616/0

Lofroth, Eric. 1998. The dead wood cycle. In: Conservation biology principles for forested landscapes. Edited by J. Voller and S. Harrison. UBC Press, Vancouver, B.C. pp. 185-214. 243 p.

Sutherland, Ira J., Elena M. Bennett, and Sarah E. Gergel. “Recovery trends for multiple ecosystem services reveal non-linear responses and long-term tradeoffs from temperate forest harvesting.” Forest Ecology and Management374 (2016): 61-70.

Thanks for sharing this interesting information! That tall grand fir and the giant big leaf maple rival some of the tallest and largest of those species in the U.S. Must visit the UBC campus next time I go through Vancouver.

Yes indeed, and they are very convenient to visit. Let me know when your in town and we’ll go find, measure, and climb some tall trees!

Pingback: Vancouver firefighters put out brush fire at Wreck Beach - News Canada

What about the big trees located in Queens Park in New West. Should they not be part of the “old growth” as well??

Thanks for your question, Paul. I’m not familiar with the forest there. I wonder if they are rapidly growth second-growth (lots around) as opposed to old-growth. It’s remarkable how tall 100 year old Douglas-firs can be. Nonetheless, if there are big trees there, I’ll try to make a trip out.

Pingback: Vancouver firefighters put out brush fire at Wreck Beach | Lokalee - Trusted Reviews & Ratings On Your Local Business Directory - USA - Canada

Really cool stuff. 63 – 67 m grand fir is impressive! All those massive fir and cedar stumps 2 to 3 meters diameter I think reinforce the size of the ancient forest that was once Vancouver. Have you encountered any Douglas fir stumps that exceeded 3 meters DBH?

Fantastic work and awesome photos! Sounds like you are finding some new potential record trees in the area of Vancouver! Cheers.

Thanks Micah! I think the unbelievable thing is that we’ve got trees over 60m in height here that are only 90-110 years old. How tall could they grow here after 200 years? After 500 years? And so on… just imagine

I’d like to say that only time will tell… but, in reality, I feel optimistic that the historical research being done by people like you Micah, are already starting to yield more and more accurate estimates of historical tree heights.

Great read! Well now I have some places to go the next time I get a chance to go out to UBC, because I haven’t seen a lot of what you have documented here, save for the trees featured on the tour I went on with you, and Ralf and company. Interesting what Paul was saying about Queens Park, I recall seeing some fairly impressive trees there back in the early 80s but that was before I was hunting big trees. My curiosity is definitely piqued

Thank-you for this comprehensive study of these important ‘Elder’ beings.

As an Arborist with the UBC Garden Shop I worked with Jeff Burton and Colin Varner to catalogue Campus trees. It was difficult to watch as significant Arboricultural specimens were constantly being lost to Development. UBC Govenors need to replace ‘profit’ with ‘preservation’ as the new mantra. And as an institution of higher learning, have they not heard of Global warming?

All My Relations

Pingback: Spanish Trail to Salish Trail Loop in Pacific Spirit Regional Park – Outdoor Family